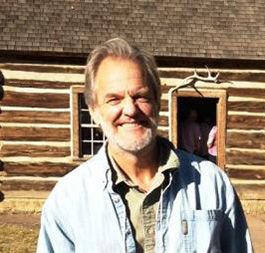

Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas: Jeffrey Ostler

January 12, 2021 by David

Filed under Non-Fiction, WritersCast

Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas – Jeffrey Ostler – 9780300255362 – Yale University Press – Paperback – 544 pages – September 22, 2020 – $25 – ebook versions available at lower prices

Surviving Genocide: Native Nations and the United States from the American Revolution to Bleeding Kansas – Jeffrey Ostler – 9780300255362 – Yale University Press – Paperback – 544 pages – September 22, 2020 – $25 – ebook versions available at lower prices

“A landmark book essential to understanding American history, Surviving Genocide is an act of courage. Ostler’s brilliant concept of reconstructing ‘an Indigenous consciousness of genocide’ is significant for its insight into how American Indians understood, discussed, and resisted genocidal threats to their families, communities, and nations. His modern vocabulary of ‘atrocities’ and ‘killing fields’ is not for political effect but appropriate to the brutal reality of Indian policy in American history.”—Brenda Child, Northrop Professor of American Studies, University of Minnesota

Even though many of us feel we are familiar with the story of the “settling” of America by Europeans and the dispossession of indigenous people, reading Jeffrey Ostler’s book, part one of a major two-volume history, will educate every single one of us to a better understanding of the full scope of the takeover of a continent by invading Europeans. Conquest and genocide are terms we seem unable to apply to our own history, preferring still a more sanitized version of the centuries long overwhelming of the people who lived here before Europeans arrived in force.

Ostler has spent years of research documenting the governmentally sanctioned use of force to remove or kill the indigenous people who were inconveniently in the way of the relentless expansion of the American republic. In this book he documents the losses from the violence – massacres, destruction of habitat and lifeways, diseases and cultural upheaval suffered sequentially by native peoples for hundreds of years as first colonial settlers and then Americans flooded the continent. This volume covers the story of the eastern United States from the 1750s to the beginning of the Civil War that set the stage for the post-Civil War expansion that is perhaps the better known narrative – buffalo, horses, trains, Crazy Horse and the Lakota being so much a part of popular culture imagery. As Ostler shows, the way this played out was not “inevitable” and Manifest Destiny was neither. The indigenous people were outnumbered, but often not out maneuvered or outwitted, and their ability to survive the nightmares of dispossession and attempted genocide is heroic.

As Americans, it is sometimes difficult to look at our own history with honesty. It is often said that the “original sin” of America is slavery, but I think we must grapple with the actuality that there are two essentially economic-based social and cultural wounds at the heart of the American project. First, there is the forced dispossession of the people who were on the land itself, and second, the forced migration and enslavement of Africans for the benefit of white Americans and their economic development. We must learn as much as we can about the history of the last five hundred years in North America in an unromanticized, clear-eyed effort to fully comprehend what our forebears did in the course of creating the American dream all of us are allowed thereby to enjoy. The truth in all its complexity should serve as counterweight to the false narratives and self-serving images we choose to live by, all created as a form of ongoing social control.

Indigenous people have survived despite the many attempts to extirpate them or to forcibly transform and bend their cultures into the conquerors’ image of what “civilization” looks like. Still, the traumatic effects of conquest need to be recognized, acknowledged and repaired and it would be no small thing to recognize formally that a genocide was in play, with all the social and political results that term carries with it. This book and presumably the subsequent volume in Ostler’s work, should help us move in that direction.

The book is well written, hard to put down and completely engrossing; its authoritative and well-researched approach makes it a powerful document and well worth your time to read.

I’m grateful for Jeffrey Ostler for taking the time to talk to me about this book and for Yale University Press for alerting me to it.

Jeffrey Ostler is Beekman Professor of Northwest and Pacific History at the University of Oregon and the author of The Lakotas and the Black Hills and The Plains Sioux and U.S. Colonialism from Lewis and Clark to Wounded Knee.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

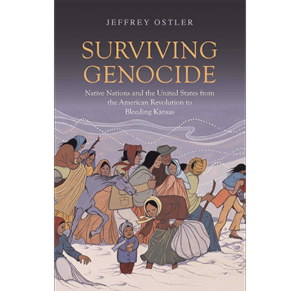

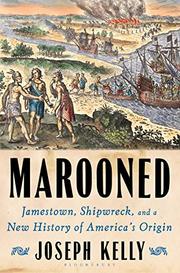

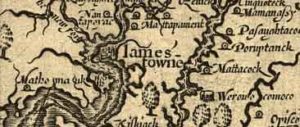

Joseph Kelly: Marooned: Jamestown, Shipwreck, and a New History of America’s Origin

March 18, 2019 by David

Filed under Non-Fiction, WritersCast

Marooned: Jamestown, Shipwreck, and a New History of America’s Origin – Jospeh Kelly – 978-1-63286-777-3 – Bloomsbury – Hardcover – 512 pages – $32 – October 30, 2018 – ebook versions available at lower prices

Marooned: Jamestown, Shipwreck, and a New History of America’s Origin – Jospeh Kelly – 978-1-63286-777-3 – Bloomsbury – Hardcover – 512 pages – $32 – October 30, 2018 – ebook versions available at lower prices

I really enjoy reading books about American history, and especially lately, books that explore some of the stories and moments that are foundational to the history of this continent, but are not well known or well told. And I’ve also become extremely concerned about gaining a better and more nuanced understanding of those stories that have been told solely from the perspective of the European (white) perspective that dominates our historical narrative, and thus our understanding of ourselves.

Joseph Kelly’s Marooned is just such a book, and I was immediately drawn to it. This is an insightful re-examination of the 1607 Jamestown settlement, the story of which really should replace the Mayflower colony’s position as America’s founding Puritan-centric myth.

In fact, the multiple stories of Europeans’ initial contact with the native peoples who fully inhabited North, Central and South America all require a complete re-examination, and I have been reading several books that provide insight into the way these continents were conquered by the marauding Europeans and their violence and diseases.

Marooned is about much more than just the Jamestown settlement. The book begins by recounting the settlement’s really awful circumstances. Most of those early settlers died of disease or starvation or deserted to the local tribes for protection. The workings of the Virginia Company that was set up to colonize and exploit the supposedly “virgin” New World are fascinating and in some ways depressingly familiar to our modern large scale version of unrestrained capitalism.

The traditional blame for the miseries of Jamestown’s early years goes to those leaders who failed to manage their “lazy” colonists, as opposed to those who were ready, willing and able to literally whip them into shape. But Kelly makes it clear that because it was the aristocrats who wrote the documents on which our traditional history relies, the real story may be, likely is, significantly different. Kelly finds ample evidence that the colonists who were cast into the wilderness, “marooned” from home and trying to survive, experienced a far different reality than their leaders. Many of them had a nascent understanding that Britain’s rigid class structure would not work in this different environment, and that their actual survival required a far more equitable system of governance. In fact, there were many uprisings and expressions of rebellion, all of which were put down, although a limited electoral oligarchy emerged during the course of the 17th century in the Virginia colony.

There are many side trips and journeys throughout this engaging narrative. The story of the castaways from one of the resupply ships on Bermuda, truly a story of being marooned, is striking. Nine ships en route to re-supply Jamestown in 1609 were hit hard by a hurricane, a storm of extreme high winds and waves, and one ship, the Sea Adventure, with some of the key leaders of the expedition on board, was wrecked on the shores of the Bermudas. The crew reached one of the islands in safety, and almost a year later, after building two boats by hand, they sailed again for Jamestown, and somewhat surprisingly, were able to reach their destination not long after departing from Bermuda. This story circulated widely in London, and may well have inspired Shakespeare’s great play, The Tempest. The timing is certainly right for that to be the case.

Kelly contributes a significantly better understanding of the Powhatan Confederacy’s formation and politics before and during the settlement period, as well as the fluidity between the cultures of the native peoples and the colonists. Marooned is not just the story of the Europeans and their conquest, but successfully weaves together the the narrative of the struggles of native peoples of that time and place in their powerful efforts to survive the arrival of the brutal land grabbing English settlers and the lives of the colonists at the lower ends of the social strata, whose stories we rarely, if ever, get to know.

It is a pleasure to discover such a good writer and story teller as Joe Kelly is. In this book, he truly brings history alive through its people, and with a narrative built on a solid grounding of research and a deeper understanding of the complexities of perspective than many other historians.

Joseph Kelly holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Texas, Austin, and is a professor of literature and director of Irish and Irish American Studies at the College of Charleston. He is the author of America’s Longest Siege: Charleston, Slavery, and the Slow March Toward Civil War, and the editor of the Seagull Reader series. He lives in Charleston, South Carolina. Joe’s blog can be found here.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Colin G. Calloway: The Victory with No Name

January 2, 2017 by David

Filed under Non-Fiction, WritersCast

The Victory With No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army – Oxford University Press – paperback – 214 pages -978-0190614454 – $16.95 (ebook versions available at lower prices)

The Victory With No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army – Oxford University Press – paperback – 214 pages -978-0190614454 – $16.95 (ebook versions available at lower prices)

I think it’s safe to say that most Americans have not given much thought to the very early history of the United States. During the first decades after the country was formed, there was much concern about the survival of the new nation. The British were still well established in the north, the Spanish were in the south and southwest, and large numbers of Indians inhabited the vast area to the west. Pressure was being exerted on the federal government to open these western lands to settlement, putting the US on a collision course with the natives who lived there.

This area was known as the Northwest Territory – comprising what are now the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota. Almost all Americans dismissed the land claims of the Native Americans. These tribes they saw simply as impediment to American growth. While some American leaders preferred to purchase the Indians’ land, the need for the government to pay its debts by selling (Indian owned) land overwhelmed all other concerns, and led ultimately to a war of extermination with the tribes.

Historian Colin G. Calloway is exceptionally perceptive and knowledgeable about the early history of the United States of America. This short, well written book focuses on a single unnamed battle that took place in late 1791 in what is now Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this period, before there was a standing army, President George Washington ordered Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, to direct a military campaign aimed at defeating the tribes that had refused to accept the unfair land deals the United States had proposed to them.

Calloway shows that the Native Americans were well organized and well-led, both politically and militarily. This surprised St. Clair as much as it may surprise us today. The American Indians were led by Little Turtle of the Miamis, Blue Jacket of the Shawnees and Buckongahelas of the Delawares (Lenape). Their war party numbered more than one thousand warriors, and included a large number of Potawatomis from eastern Michigan, a broad confederacy presaging similar Indian efforts to come in later years.

As Calloway points out: “Indians fielding a multinational army, executing a carefully coordinated battle plan worked out by their chiefs, and winning a pitched battle—all things Indians were not supposed to be capable of doing—routed the largest force the United States had fielded on the frontier.” It’s useful to note that the American army was poorly organized, included a large number of ill-trained militia, and was also victimized by crooked suppliers, starting a longstanding American tradition of private gain by military purveyors we recognize all too well today.

Unfortunately for the Native Americans, their victory was short lived. The stunning American defeat led directly to a number of changes in the way the new government operated. The House of Representatives initiated the first investigation of the executive branch, Congress established a standing army and gave the president authority to wage war. A liquor tax was created to finance the Army (which led to the Whiskey Rebellion that ironically, President Washington used the tax-financed militia to put down). The Indian confederacy did not last, and in 1794, General “Mad Anthony” Wayne built Fort Recovery and defeated another Indian war party at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, ultimately bringing an end to Northwest Territory Indian resistance and opening the way for the first stage of westward growth of the new American nation.

There is so much interesting history that relates directly to the story told in this book. It’s a compelling read for anyone interested in the early period of the American republic. My conversation with Colin Calloway reflects the stirring nature of his book, and the breadth of his knowledge. This book is an important American story, well told, and I highly recommend it.

Colin Calloway is the author of a number of excellent works, including one of my personal favorites, One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West before Lewis and Clark. He is the John Kimball, Jr. 1943 Professor of History and Professor of Native American Studies at Dartmouth, where he has taught since 1990. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Leeds in England.

Length note – this interview is slightly longer than average at about 35 minutes.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download